Wadden,

Mary F.

Wallace,

Julia (Abernethy)

Warrior,

Betsy

Whitman,

Florence (Lee)

Whitney,

Anne

Williams,

Antoinette (Rinaldi)

Window

Shop

Winship, Joanna

Winthrop, Hannah (Fayerweather)

Wise, Ozeline Barrett (Pearson)

Wise, Pearl (Katz)

Wolf, Alice K.

Women's Center (aka Women's Educational Center,

Cambridge Women's Center)

Women's Coffeehouse

Women's Community Health Center

Women's Law Collective

Women's School of Cambridge

Mary

F. Wadden

(b. ca. 1925, d. March 25, 2001)

Teacher

Mary Wadden was the daughter of Dr. Joseph M. Wadden and Mary F. (McBride) Wadden.

She was a lifelong resident of Cambridge and taught in the Cambridge Public

schools for thirty-eight years. The Cambridge City Council passed a resolution

in recognition of her life and achievements on April 2, 2001.

Reference: City Council resolution, April 2, 2001

Return

to Top of Page

Julia

Abernethy Wallace

(b. May 16, 1936, in Shelby North Carolina, d. Jan. 3, 2010 in Cambridge, Mass.)

Teacher, Human Rights Activist, Volunteer

Julia

Abernethy Wallace was the daughter of Ethel (Thomas) and Walter Eugene Abernethy.

She grew up in Shelby, North Carolina. She attended Meredith College in Raleigh,

where she met her future husband, James (Jim) Wallace with whom she shared a

life-long commitment to social justice and instilled the same values with their

children. She accompanied Jim to Cornell University, then to Los Angeles, where

she worked as a youth advisor at a local church. The family then moved to Buffalo,

New York, where Julia received a Masters degree in education. After they moved

to Cambridge, she obtained a second Masters as a reading specialist and then

taught remedial reading for many years in the Cambridge public schools.

Julia

Abernethy Wallace was the daughter of Ethel (Thomas) and Walter Eugene Abernethy.

She grew up in Shelby, North Carolina. She attended Meredith College in Raleigh,

where she met her future husband, James (Jim) Wallace with whom she shared a

life-long commitment to social justice and instilled the same values with their

children. She accompanied Jim to Cornell University, then to Los Angeles, where

she worked as a youth advisor at a local church. The family then moved to Buffalo,

New York, where Julia received a Masters degree in education. After they moved

to Cambridge, she obtained a second Masters as a reading specialist and then

taught remedial reading for many years in the Cambridge public schools.

Both Julia and Jim were active in the Old Cambridge

Baptist Church, In the early 1970s, they became founding members of the cooperative,

Commonplace, on Oxford Street in Cambridge where she lived for the rest of her

life. Jim and Julia worked for many peace and social justice causes and hosted

refugee families from Chile and El Salvador, sometimes for as long as a year,

during the periods of oppression in Central and South America. They both were

active in the Sanctuary movement (1985 – 1990) and Julia accompanied Estela

Ramirez/Magdalena Rivas while she presented her talks on the movement. Julia

sat on the Cambridge-San José las Flores sister city committee (1986

– 2009), often traveling to San Salvador to encourage democratic development

and cultural exchange.

Toward the end of her life, stricken with Alzheimers,

she continued to work to the best of her ability with different disadvantaged

communities. She was awarded the Msgr. Romero Peace Award by Centro Presente

in March 2009. A memorial after her death allowed many of these organizations

to celebrate her life. One of the organizations she worked with, Adbar Ethiopian

Women's Alliance, with the cooperation of a number of other immigrant and social

justice organizations, created a quilt in her honor which was hung on display

at the Cambridge Public Library in Central Square. A program, sponsored by the

Cambridge Women's Heritage Project, using this quilt as a departure point, was

presented in honor of the immigrant Cambridge women who work for social justice,

on International Women's Day, March 8, 2012.

References:

Obituary Boston Globe, January 5, 2010.

Family information.

Return

to Top of Page

Betsy

Warrior (b. 1940, Boston)

Feminist, Human Rights Activisst, Tenant's and Welfare Rights Organizer

Nominated by Chris Womendez

Betsy

Warrior was a radical activist and organizer of women’s liberation and

the battered women’s movements in Cambridge, Boston and the nation. In

1968 she began organizing and agitating as one of three original members of

Cell 16, a women’s liberation group that exposed the subordination of

women and advocated for equal pay, childcare, reproductive rights, economic

justice and self-defense. These early messengers for women’s rights campaigned

against unpaid labor by homemakers, wife abuse, exposed the inequality of women

in the workforce and in intimate relationships and they trained women in karate

for self-protection. She was an author and editor of the Journals of Female

Liberation.

Betsy

Warrior was a radical activist and organizer of women’s liberation and

the battered women’s movements in Cambridge, Boston and the nation. In

1968 she began organizing and agitating as one of three original members of

Cell 16, a women’s liberation group that exposed the subordination of

women and advocated for equal pay, childcare, reproductive rights, economic

justice and self-defense. These early messengers for women’s rights campaigned

against unpaid labor by homemakers, wife abuse, exposed the inequality of women

in the workforce and in intimate relationships and they trained women in karate

for self-protection. She was an author and editor of the Journals of Female

Liberation.

Often, in the late sixties, Warrior

could be found disseminating feminist literature written by Cell 16 on the streets

of Cambridge in Harvard Square. At that time, promoting the ideas of female

liberation met with hostility or ridicule. As people began reading and arguing

these ideas some attitudes began to change, and women especially began to drop

their denial of male supremacy and support feminist perspectives. This street

agitation served an important role in broadcasting ideas, as not only the corporate

press, but also alternative presses were male controlled, virulently sexist,

and women, as usual, lacked the financial resources to compete with the male

propaganda machines. Distributing literature on the street was one way to foil

male suppression of this female insurrection.

In 1969 Warrior’s economic

analysis of women’s unpaid labor: Housework: Slavery or a Labor of Love

and The Source of Leisure Time was published. In Housework, she posited that

wife beating was an occupational hazard of the housewife who, deprived of monetary

remuneration for her labor, lacked resources and recourse to escape male-pattern

violence. In Leisure Time she described how women create leisure time for others

by performing most of the life sustaining, arduous tasks necessary for everyday

existence, thus freeing others for more creative endeavors. In 1971 Warrior

and Lisa Leghorn wrote and edited the Houseworker's Handbook, an economic analysis

of the unpaid labor of houseworkers, which makes inevitable women’s lack

of economic leverage in the paid labor force - and in every other sphere It

is this economic disenfranchisement that creates a breeding ground for abuse.

How much are employers willing to pay workers who characteristically work for

free? Three editions of the Handbook were published.

On International Women’s Day,

1971 Betsy marched from Boston to Cambridge in a demonstration to demand a center

for women. Some of the demonstrators took over a Harvard building until they

were given space for a Women’s Center at another location. At the new

Women’s Center, Betsy built and stocked a library of books on women’s

struggles for self-determination, provided GED classes, and explored options

for starting a women’s press. Simultaneously, she was active in welfare

rights and tenant’s rights organizing. In 1974, while working with Chris

Womendez and Cheri Jimenez, who established the first shelter dedicated to battered

women, and with Respond, another shelter group, Warrior realized the need for

a compendium of resources, analyses of male-pattern violence and templates for

shelter procedures so she undertook a decade long effort to provide a network

to knit the shelter movement together by sharing resources and knowledge.

As a result, Warrior wrote, edited

and published Working on Wife Abuse (later called Battered Women’s Directory),

which was the first international directory of individuals and programs advocating

for battered women. It provided statistics on wife abuse, articles on the history,

motivations and utility of male-pattern violence, explained legal options like

restraining orders, offered articles by men working to combat sexism by counseling

abusive men and provided a bibliography on woman abuse as well as advice from

emergency room doctors treating battered women. It included guidelines for setting

up shelters, hotlines and support groups for battered women. Nine editions were

published. The first edition was 33 pages and the last, in 1989, was 300. The

Schlesinger Library for Women at Harvard houses her "collection" which

contains some of her correspondence with people setting up shelters and services

in the early years. http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~sch00439

Warrior was born in Boston's

South End in 1940, the child of Canadian immigrants. Married at 17, she endured

years of abuse (as is the case for millions of women even today) by her husband

before being able to leave with her child. Thereafter, she adopted the name

“Betsy Warrior” to commemorate a Native American activist. She identifies

as a working-class woman of multiple ethnicities, including Canadian Micmac,

and is self-educated. To support her activism Warrior worked in factories, at

a gas station, as a janitor, and finally, for many years, as a librarian. She

worked at the Women’s Center for nearly 40 years providing advocacy and

support for battered women and training for other women and agencies to facilitate

such groups.

In 1985, Betsy and other

activists attempted to place an anti-pornography Human Rights Ordinance on the

ballot in a Cambridge election. When the city refused, the women sued the city

and won. The referendum was placed on the ballot, but was narrowly defeated.

If such an amendment had succeeded in being enacted, it could have allowed people

harmed by pornography to sue its publishers, providing a useful instrument to

protect women and children who are subjected to pornography as a “seasoning”

tool to inure them to sexual abuse and trafficking, and for men who become unwittingly

addicted to pornography.

In 1987 Warrior won an award from

Boston Woman’s magazine for bettering the lives of women in the Greater

Boston area. In 1991 she received recognition for her work with Finex House

and the first Jane Doe Unsung Hero Award was given Warrior in 1993. In 2007

Women’s ENews also recognized her work in widely fostering and networking

shelters for battered women calling it “The Betsy Warrior Effect.”

Starting in 2001 Warrior also worked with Adbar the Ethiopian Woman’s

Alliance for a decade helping design layout for their newsletter “Mela,”

editing and fielding articles as well as designing a logo for the Ethiopian

Alliance’s Sheba enterprise.

During her years as a human rights

activist, Warrior also designed some iconic posters for the feminist movement

including “Strike While the Iron is Hot: Wages for Housework,” “Disarm

Rapists: Smash Sexism,” “For Shelter and Beyond.” Recently,

Betsy developed a series of International Women’s Rights Posters honoring

women activists from many continents. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VN7qpEEw1Ow

). She has also posted some of her watercolors on YouTube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IZIGGp6SBtQ.

Many of Betsy’s books and articles are now out of print. In the future,

she is hoping to post them on the web for ready access by feminists and others

working to end male violence against women.

“Betsy Warrior was

more than an inspiration to the early battered women’s movement. She provided

critical analysis of “male-pattern violence,” offered support to

struggling feminists establishing women’s centers and shelters, and established

a broad, international network of women and men activists committed to ending

men’s violence toward women. To say we are profoundly indebted to her

vision, passion and dedication is an understatement. Her contributions are beyond

comprehension and certainly far exceed this modest herstory of Betsy Warrior.”

Barbara J. Hart, J.D. - Director of Strategic Justice Initiatives,Muskie School

of Public Service, Portland, Maine, August 2013.

References:

Personal Interview by Sandra Pullman, January 2003;

Betsy Warrior’s work on battered women is cited in R Emerson Dobash, Women,

Violence and Social Change, Routledge 1992 and R. Amy Elman Sexual

Subordination and State Intervention: Comparing Sweden and the United States.

Berghahn Books. 1996;

Her work with Cell 16 and the Women’s

Center is discussed in Flora Davis, Moving the Mountain: The Women's

Movement in America Since 1960. Simon and Schuster, 1991.

Additional

References

and Citations provided by Betsy Warrior with revised bio in Aug 2013:

“Wife

beating is now a media “cause.” With all the platitudes and T.V.

dramas, it’s especially important we remember the women who started it

all. Betsy Warrior’s Battered Women’s Directory is part of that

history and an assurance that feminists will be there long after the cameras

and reporters have gone. Betsy Warrior has been doing key feminist work and

writing since the sixties, publishing the Houseworker’s Handbook and in

the Journal of Female Liberation. Her 1974 article Battered Lives helped start

a movement in the U.S. The first Battered Women’s Directory, formerly

called Working on Wife Abuse, appeared in April 1976. Some of this should be

required reading for feminists in every sort of organization. Feminist vision

is needed more than ever. The Battered Women’s Directory provides this.

Sections on running a shelter, support group, or hotline are models both for

these specifics and for general feminist principles, such as self-help. And

the listings! First of all, there are over 150 annotated references to films

and publications. It’s most exciting though to see the list of groups

and individuals – abroad and in all 50 states. Here at a time when people

claim the women’s movement is dead are the names of over a thousand groups

and individuals – just working on this issue alone!” Molly Lovelock,

Sojourner News, Cambridge MA 1978

Schlesinger Library, Harvard

University: Betsy Warrior Collection. http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~sch00439

21 Leaders Gala Celebrates 'Betsy Warrior' Effect, By Rita Henley Jensen, WeNews

Editor in Chief, 5/ 22/07 http://womensenews.org/story/21-leaders-the-21st-century/070522/21-leaders-gala-celebrates-betsy-warrior-effect#.UfguzqzYG3M

In Our Time: Memoir of a

Revolution, by Susan Brownmiller, Dell Publishing (Nov. 2000)

Notes from the Third Year:

Radical Feminism, Anne Koedt, and Ellen Levine (1972)

Women, Violence and Social

Change, by R Emerson Dobash, Pub. Routledge (1992)

Radical Feminism, Anne Koedt,

Ellen Levine, and Anita Rapone (eds.), Quadrangle Times Books (October 1973)

Feminists Who Changed America:

1963–1975. Univ. of Illinois Press, Barbara J. Love and Nancy F. Cott.

(2006).

Pioneers of Women's Liberation:

In Voices of the New Feminism. Edited by Mary Lou Thompson. Boston: Beacon Press.

(1989)

Voices from Women’s

Liberation, Leslie Tanner, Signet, (1970)

History of the Battered

Women’s Movement, Indiana ICADV (2009) http://www.icadvinc.org/what-is-domestic-violence/history-of-battered-womens-movement/

Voices of the New Feminism.

Ed. Mary Lou Thompson. Boston: Beacon Press (1970)

Moving the Mountain: The

Women's Movement in America since 1960, By Flora Davis, University of Illinois

Press, 1999

Framing the Victim: Domestic

Violence, Media, and Social Problems, By Nancy Berns, Transaction Publ. NJ (2004

& 2009)

Women and Male Violence:

The Visions and Struggles of the Battered .Woman’s Movement, by Susan

Schechter (1982)

From Thought to Theme: Reader

for College English, by William Smith and Raymond Leidlich, Harcourt, Brace

Jovanovich (6th edition 1980)

Women's Movements Facing

the Reconfigured State, by Lee Ann Banaszak, Karen Beckwith, Dieter Rucht -

Political Science (2003)

Sexual Subordination and

State Intervention: Comparing Sweden and the United States. By R. Amy Elman,

Berghahn Books. 1996

From Amazon online: http://www.amazon.com/Battered-Womens-Directory-Betsy-Warrior/dp/0960154469

5.0 out of 5 stars Women's history and practical political information, February

17, 2000

By jay (Halifax, Nova Scotia) - review of Battered Women’s Directory (Paperback)

“The Battered Women's Directory is an excellent source for information

on the historical, political and economic background of violence against women.

Although it seems written initially as a directory of services for battered

women, the 100 pages of text it includes makes it a feminist classic on the

movement against violence towards women. In fact, much of the directory for

services is now out of date. Still, the political analysis is as trenchant as

ever. The text includes a wide selection of articles from various perspectives.

For instance, articles written by medical professionals give us the view of

the battered woman from an emergency room perspective. Other articles, by batterers

and by the men who counsel them, give deep insight into some of the emotional

forces triggering this behavior. Best of all, are the articles written by the

book's author whose concise style and well-expounded arguments bring a clear

understanding to this usually disputatious subject. A classic of feminist scholarship

- well worth reading!”

“One of the major

issues that has been studied and analyzed in feminist theory is the unrecognized

and unremunerated work that women do in the course of domestic work and reproduction.

Betsy Warrior’s The Houseworker’s Handbook analyzes how this unpaid

labor by women that includes housework, childcare, and care of the senior members

of the family, that many a time takes up the whole life of women, is not validated

and leads to the economic deprivation and dependence of women later in life.

The study of feminist theory has led to many movements across the world to raise

an awareness of the need to have women adequately and respectfully compensated

for their work and the need for a dignified, independent life for everyone.”

Karishma J. Anand, Thrissur (Trichur), Kerala State, India

Return

to Top of Page

Florence

(Lee) Whitman (b. September 4, 1862 in Canton, NY, d. November

22, 1948 in Cambridge)

Politician (First woman elected to Cambridge City Council)

Florence Josephine Lee was born on 4 September 1862 in Canton, New York, to

John Stebbins Lee (born in Vermont in 1820) and Elmina (Bennett) Lee (born in

New Hampshire in 1821). John S. Lee was Principal of the Preparatory Department

at St. Lawrence University in Canton, which helped to prepare students for the

university’s Theological School. (Florence’s brother, John, later

became the university's president.) Oddly, a fraternity that now occupies the

Lee family's Canton house claimed Florence as its resident ghost, believing

she had died there tragically and her “mischievous, teasing wraith”

haunted the house. In fact, Florence was a graduate of St. Lawrence and later

a member of its board of trustees. Whitman Hall on the campus is named for her

and her husband.

Florence Josephine Lee was born on 4 September 1862 in Canton, New York, to

John Stebbins Lee (born in Vermont in 1820) and Elmina (Bennett) Lee (born in

New Hampshire in 1821). John S. Lee was Principal of the Preparatory Department

at St. Lawrence University in Canton, which helped to prepare students for the

university’s Theological School. (Florence’s brother, John, later

became the university's president.) Oddly, a fraternity that now occupies the

Lee family's Canton house claimed Florence as its resident ghost, believing

she had died there tragically and her “mischievous, teasing wraith”

haunted the house. In fact, Florence was a graduate of St. Lawrence and later

a member of its board of trustees. Whitman Hall on the campus is named for her

and her husband.

On 27 June 1895 in Canton, New York, Florence married Edmund

Allen Whitman, who was born in 1860 in KS. By 1896, the couple was living at

23 Everett Street in Cambridge. The house is now occupied by Harvard Law School.

Edmund Whitman was an 1881 graduate of Harvard College. He practised law in

Boston. He was a supporter of the environmental movement as well as an outspoken

proponent of prohibition enforcement. He died in 1952.

The Whitmans' three children were born in Cambridge:

Allen Lee Whitman in June 1897, Frederic Bennett Whitman in September 1898,

and Eleanor Whitman in 1902.

Florence Whitman was a clubwoman and frequent

public speaker at the Cantabrigia Club, League of Women Voters, and area churches.

She would speak on topics such as woman suffrage, Americanization, and temperance.

She began her political life as a member of the Cambridge School Committee.

First elected in 19xx, she served on that board for 8 years. After the passage

of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, she attended the first conference for politics

and government sponsored by Smith College and the Massachusetts League of Women

Voters in the spring of 1923. That fall she ran for and was elected to a two-year

term on the Cambridge School Committee. In 1925, Whitman became the first woman

elected to the Cambridge City Council. She served a single two-year term. She

died at home in 1948, aged 86 years.

Image printed in

the Cambridge Tribune, March 31, 1923.

Resources:

St. Lawrence University website, http://web.stlawu.edu

pages from the Sesquicentennial celebration

"Ghost Stories" http://www.stlawu.edu/150/ghosts.htm

"Hail to the Chiefs: A Brief Look at Many of SLU's Leaders" http://www.stlawu.edu/150/presidents.htm;

Burks, Sarah L. Cambridge Historical Commission memo re: 23 Everett Street,

23 June 2005.

"League of Women Voters Meet In Third Conference," Cambridge Tribune,

March 31, 1923.

Return

to Top of Page

Anne

Whitney (b. September 2, 1821 in Watertown, Massachusetts; d.

January 23, 1915 in Boston, Massachusetts)

Sculptor, poet

Anne Whitney was the daughter of gentleman farmer

Nathaniel Whitney and his wife Sarah (Stone). Her family moved from Watertown

to East Cambridge in 1833, where her father was a justice of the peace. She

was educated by private tutors and attended a girls' school in Bucksport, Maine.

Soon after, at the age of twenty-five, she opened a school in Salem which she

ran for two years. She began to publish her poetry in the Atlantic Monthly

and Harpers’ Magazine, collected in a volume entitled simply,

Poems (New York, 1859), but her interest turned to sculpture. She studied

with the sculptor, and painter, William Rimmer, in Boston. In that same year

that her book of poetry appeared, she opened a sculpture studio in the backyard

of her family home. Subsequently, she made several visits to Rome where she

studied for four years, producing two of her best works during that time. She

became acquainted there with the American women sculptors, Harriet Hosmer and

Edmonia Lewis.

On her return from Europe in 1873, she established

a studio in Boston. There she executed busts, medallions, and statues, including

a statue of Samuel Adams (for which she traveled to Paris to study), of which

two copies, one in bronze and one in marble, are respectively in the capitol

at Washington and in Boston (1863). Among her works, were statues and portrait

busts of well-known women, including Harriet Martineau, (presented to Wellesley

College but destroyed in a fire) Lucy Stone, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Her

statue of Charles Sumner, completed when she was eighty, is in Harvard Square.

Her anonymous entry in the 1875 design competition for the Sumner statue was

first selected and then disqualified by the judges when they learned it had

been designed by a woman. With the support of friends, she completed the statue

in 1902, and it was installed in Cambridge rather than Boston.

She

was an active member of the woman suffrage movement and was a close friend as

well as a cousin of the activist, Lucy Stone. She lived in Boston and summered

in the White Mountains in Shelburne, New Hampshire until her death in 1915.

She is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge. Her papers are held in the

Wellesley College Archives.

References:

Appleton’s Encyclopedia

Reitzes, Lisa B. “The Political Voice of the Artist: Anne Whitney's "Roma"

and "Harriet Martineau". American Art, 8, (2) 44-65; (Spring,

1994);

Notable American Women vol. 3 (1950)

Anne Whitney Papers, Wellesley College Archives

Martin, Elizabeth and Vivan Meyer. Female Gazes: Seventy-Five Women Artists.

Toronto: Second Story Press, 1997.

Return

to Top of Page

Antoinette

(Rinaldi) Williams

(b. August 24, 1921)

Factory worker, PTA president, Volunteer

Born

in Cambridge on Howard Street, Antoinette (Toni) Rinaldi’s family moved

to Western Avenue in 1927. She attended Houghton Grammar School until 1935 and

then Cambridge High and Latin School from 1935-1939. Toni was a USO hostess

at the Cambridge Neighborhood House, then at 79 Moore Street, from May 1942

to July 1945. She met her husband, Irvin Williams, at the first dance, and they

were married on July 22, 1945. During the Second World War, Toni worked at the

silk mill in Brighton, where she wound thread for gunpowder bags, and at Dewey

and Almy Chemical Co. in Cambridge, making and inspecting target practice balloons.

She also worked at American Science & Engineering, Honeywell, and Bentley

and Babson colleges until her retirement in 1964.

Born

in Cambridge on Howard Street, Antoinette (Toni) Rinaldi’s family moved

to Western Avenue in 1927. She attended Houghton Grammar School until 1935 and

then Cambridge High and Latin School from 1935-1939. Toni was a USO hostess

at the Cambridge Neighborhood House, then at 79 Moore Street, from May 1942

to July 1945. She met her husband, Irvin Williams, at the first dance, and they

were married on July 22, 1945. During the Second World War, Toni worked at the

silk mill in Brighton, where she wound thread for gunpowder bags, and at Dewey

and Almy Chemical Co. in Cambridge, making and inspecting target practice balloons.

She also worked at American Science & Engineering, Honeywell, and Bentley

and Babson colleges until her retirement in 1964.

Toni was president of the Ellis and Fitzgerald

schools PTA.’s in the 1950s, and she was president of the American Legion

Auxiliary to Post 27, from 1963-64 and 1978-1987. Her other activities included

serving as Den Mother of Pack 73 and 1 from the mid 1950s to the late

Antoinette Williams.

Photo courtesy of Toni Williams.

1970s and organizing five

CHLS class reunions. She plays piano by ear and often entertains area nursing

home residents. In the summer of 2004, the corner across the street from her

house was dedicated to Toni and Irvin Williams.

Reference: Oral interview by Sarah Boyer.

Return

to Top of Page

The

Window Shop (1939-1971)

The Window Shop began as a consignment shop created

by a group of women (many of them Harvard wives) who wished to help refugees

fleeing Europe. Although many of the refugees were professionals and scholars,

they often were unable to obtain positions in their own fields. The Window Shop

offered a way to earn a living within the community, hiring hundreds of individuals

over the years. It survived for almost half a century, developing into a profitable

dress and gift shop that included a restaurant and bakery. First located on

the second floor of 37 Church Street in Cambridge, it soon outgrew that location.

In November of 1939, it moved to 102 Mt. Auburn Street and opened a tea room

and bakery, soon offering a lunch as well. Donations from many individuals kept

the shop going until it could prove its viability. It was incorporated in 1941.

In the early 1940s, it was one of the few businesses in Cambridge to hire African

Americans leaving the South. In 1947, the shop moved again to 56 Brattle Street,

where it remained until 1971 enjoyed by generations of Cantabridgians, becoming

a favorite haunt of many, including the architect Walter Gropius. Eleanor Roosevelt

even wrote about the delightful food and atmosphere at the Window Shop in her

newspaper column “My Day”.

Among the women who were significant in organizing

and running the Window Shop in those early days were Elsa Brändström

Ulich, a founding board member from Sweden, who was president of the Window

Shop from 1942 until her death, Elizabeth (Cope) Aub who was a founding board

member and later president (1954-1964).: Mary Mohrer, who oversaw the dress

and gift shop, and Alice Perutz Broch, manager of the kitchen and bakery. For

a brief time, the Window Shop attempted to serve as a club house in off- periods

for refugees, but this need soon diminished. An assistance fund for the employees

that also provided scholarships for their children, was created in 1943, named

after Ulich in 1948.

For many years, the Window Shop was a profitable

and attractive restaurant and gift shop until the 1960s, when its revenues declined.

In early1972, the board decided to sell the building to Cambridge Center for

Adult Education which still is located there. The board then established college

scholarship funds, a peer-counseling program at Cambridge Rindge and Latin,

which was named in memory of Mary Mohrer, and donated the corporation's papers

to the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe. In March 2004, the Cambridge Women’s

Heritage Project celebrated the history of the Window Shop. On March 10, 2007,

the Window Shop held a meeting in honor of the publication of a book detailing

its history. The Window Shop: Safe Harbor for Refugees, 1939-1972,

was written by by Ellen Miller, Ilse Heyman and Dorothy Dahl, and published

in 2007 by iUniverse. It is available in bookstores.

References: Finding aid, The Window Shop Papers, Schlesinger

Library, Radcliffe Institute; Eleanor Roosevelt, “My Day”, May 30,

1950; Ellen Miller, Ilse Heyman, Dorothy Dahl. The Window Shop: Safe Harbor

for Refugees, 1939-1972,. Diesel books, 2007; http://www.diesel-ebooks.com/cgi-bin/item/0595849873/The-Window-Shop-eBook.html

Return

to Top of Page

Joanna

Winship (b.

1645 in Cambridge; d. November 19, 1707 in Cambridge)

First Cambridge schoolmistress

Joanna Winship was the fourth daughter of Edward Winship, lieutenant of the

Cambridge militia and his first wife, Jane (Wilkinson) Winship. Her father

had arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony with John Winthrop. She was the

first schoolmistress in Cambridge. The epitaph on her tombstone in the Old

Burying Ground in Cambridge reads, “This good school dame / No longer

school must keep / Which gives us cause. / For children’s sake to weep.”

Reference: An Historic Guide to Cambridge, Appendix “Edward

Winship”

Return

to Top of Page

Hannah

(Fayerweather) Winthrop (b. ca February 1727 in Boston d. 1790

in Cambridge)

Eighteenth century woman of letters

Hannah Winthrop was the daughter of Thomas and

Hannah Waldo Fayerweather. Although her exact birth date is not known, she

was

baptized in Boston at the First Church of Boston on February 12, 1727. She

was married twice, at eighteen years of age to Parr Tolman in 1745, and

after

Tolman's early death, to John Winthrop in 1756. Hannah and John Winthrop lived

in Cambridge, where her husband was professor

of mathematics and natural history

at Harvard University and a noted astronomer. Their house was located at

the northwest corner of Mount Auburn and John F. Kennedy streets facing the

market square, now called Winthrop Square.

Hannah provided a lively account of

her life

in Cambridge

in

a series

of letters

to

Mercy Otis

Warren

and Abigail

Adams. During the Revolutionary war, she described the flight of women and

children from the center of Cambridge as the English advanced. “We were

directed to a place called Fresh Pond, about a mile from the town, but what

a distressed

house did we find it, filled with women whose husbands had gone forth to meet

the assailants, seventy or eighty of these, with numbers of infant children,

weeping and agonizing for the fate of their husbands.” The following

year, she wrote to Mercy Warren about the eagerness with which men and women

sought

to inoculate themselves and their children against the smallpox.: "The

reigning subject is the small pox. Men, women and children eagerly crowding

to inoculate is I think as modish as running away from the troops of a barbarous

George was last year." A portrait of her in her late thirties, painted

by John Singleton Copley, is held in the Metropolitan Museum of New York.

References: Mercy Otis Warren letters, Mass Historical Society;

Kate Davies., Catharine Macaulay and Mercy Otis Warren: The Revolutionary

Atlantic and the Politics of Gender. (New York: Oxford University Press,

2005);

http://www.cambridgema.gov/~Historic/april1.html

Return

to Top of Page

Ozeline Barrett

(Pearson) Wise (b.

in Worcester, MA, in 1903; d. in Cambridge, MA in 1988)

State employee, volunteer

Ozeline Barrett Pearson was the second daughter

of Frances Lavina (Gale) and William B. Pearson. Her father moved from Jamaica

to Worcester, MA soon after the

birth of his first daughter, Satya (Pearson) Barrett. Soon after Ozeline’s

birth, the family moved to Cambridge where for many years he was pastor of St.

Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Ozeline attended Cambridge public schools and graduated from Cambridge High School.

She held clerical jobs until she married John Wise in 1931. The couple adopted

a son, Hubert Smith, in 1961. Ozeline Wise worked for the Navy during World War

II, and after the war, she was the first black woman employed by the banking

department of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, where she worked for nearly

twenty years.

During the 1950s, the Wises lived in Billerica, Mass., in a house which they

ran as an inn that they named Galehurst. Some time after her husband’s

death in 1963, she returned to Cambridge to live with her sister, Satya Barrett.

She spent much of her energy at St. Paul AME Church, serving as a Sunday School

teacher, trustee, and chair of the building fund. She worked with her older sister

Satya in many of the same community organizations, and was a charter member of

the Citizens' Charitable Health Association.

From 1965, Wise lived with her sister, who had suffered a series of strokes,

caring for her sister until her death in 1977. She contributed an oral interview

to the Black Women Oral History Project of Schlesinger Library. Ozeline Wise

died in 1988 and left her papers, as well as those of her sister and her father,

to Schlesinger Library.

References: Ozeline (Pearson) Wise papers and biographical information, Schlesinger

Library. Ozeline (Pearson) Wise interview, Black Women Oral History Project of

Schlesinger Library.

Return

to Top of Page

Pearl

(Katz) Wise (b. ca. 1901, d. August 8, 1999, in Cambridge, MA)

Cambridge community leader; politician

Pearl

Katz, the daughter of Julius Katz, was born in Kovno, Russia, in 1900 or 1901.

She emigrated with her mother and two older siblings to Connecticut in 1905,

where her father later joined them. Although she went only through high school,

she was self-educated to a remarkable degree. In 1921, the family moved to Cambridge,

and in 1927 she married a young lawyer, Henry Wise. They had three children

(two daughters and a son) who attended Cambridge schools. Beginning in 1942,

Wise became involved in public affairs. She served first as president of the

League of Women Voters of Cambridge (1942-1945). In 1945, she organized the

Parent-Teachers Association at Cambridge High and Latin School and was its first

president in 1947, working successfully to obtain federally funded hot lunches

in the schools. In 1948, she organized and led the statewide legislative campaign

of the Massachusetts League of Women Voters, fighting to allow women to sit

on juries in the Massachusetts courts. In 1945, she was elected to the Cambridge

School Committee, on which she served for three terms from 1949 to 1955. For

one of the three terms, she was the vice chair.

Pearl

Katz, the daughter of Julius Katz, was born in Kovno, Russia, in 1900 or 1901.

She emigrated with her mother and two older siblings to Connecticut in 1905,

where her father later joined them. Although she went only through high school,

she was self-educated to a remarkable degree. In 1921, the family moved to Cambridge,

and in 1927 she married a young lawyer, Henry Wise. They had three children

(two daughters and a son) who attended Cambridge schools. Beginning in 1942,

Wise became involved in public affairs. She served first as president of the

League of Women Voters of Cambridge (1942-1945). In 1945, she organized the

Parent-Teachers Association at Cambridge High and Latin School and was its first

president in 1947, working successfully to obtain federally funded hot lunches

in the schools. In 1948, she organized and led the statewide legislative campaign

of the Massachusetts League of Women Voters, fighting to allow women to sit

on juries in the Massachusetts courts. In 1945, she was elected to the Cambridge

School Committee, on which she served for three terms from 1949 to 1955. For

one of the three terms, she was the vice chair.

Pearl Wise was responsible for the establishment

of a library in each Cambridge public school. This action was memorialized by

the naming of the Cambridge Rindge and Latin School's library in her honor in

1983. In 1955, she became the first woman, since the Plan E form of city government

was adopted, to be elected to the Cambridge City Council; she served until 1963.

During this period she cast the deciding vote to reject the proposed urban renewal

project in East Cambridge, which would have razed about 150 homes. Her husband,

Henry Wise, had a long career in labor law and was a major proponent of public

housing and legislation to restrict urban renewal in Massachusetts. After Wise’s

retirement from the City Council, she worked at the Cambridge Housing Authority

for many years. Her papers are held at Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute.

References: Cambridge Chronicle, August 12,1999; Schlesinger

Library biography and guide to Pearl Katz Wise papers.

Pearl Wise.

Photo courtesy of the Wise Family.

Return

to Top of Page

Alice

K. Wolf (b. Austria)

State representative, former Mayor of Cambridge

Born in Austria, Alice came to America at the

age of five with her family who were fleeing the Nazis. She earned a B.S. from

Simmons College earned an M.P.A. degree from Harvard University’s John

F. Kennedy School of Government in 1971. She was a fellow at Harvard’s

Institute of Politics in 1994. In 2001, she received an honorary Doctor of Education

degree from Wheelock College.

She was elected to the Massachusetts House of

Representatives in 1996 after serving the people of Cambridge as Mayor (the

second woman to be elected to that position), Vice Mayor, City Councillor, and

School Committee member. Beginning her political career in 1971, she has been

active in working for early childhood education, public education, affordable

housing, health care, and has been consistently a strong advocate for women’s

rights.

Among her many honors and awards are: the 2002

Legislative Leadership Award from the Massachusetts Alliance for Arts Education,

the 2002 Margot P. Koberg Award from the Cambridge Fair Housing Committee, the

Outstanding State Legislator Award from MIRAC (Massachusetts Immigrants &

Refugee Advocacy Center), Legislator of the Year Award from the JCRC (Jewish

Community Relations Council), the 1996 Progressive Leadership Award from the

Commonwealth Coalition, and the 1993 Woman of Courage Award from the Massachusetts

chapter of the National Organization of Women. Alice and her husband Robert

Wolf have two sons, Eric and Adam.

References: www.hno.harvard.edu/gazette/2005/06.02/07-hglc.htm;

alicewolf.org/bio.htm

Return

to Top of Page

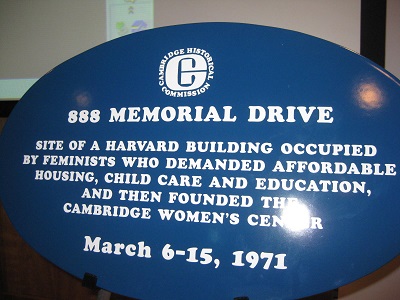

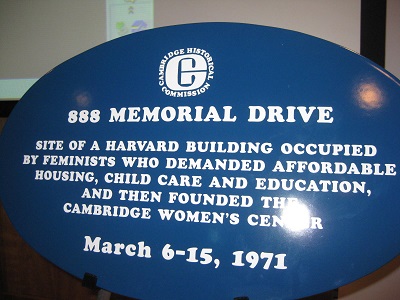

Women’s

Center (aka Women's Educational Center, Cambridge Women's Center)

Community organization, 46 Pleasant Street, Cambridge

The Women’s Center arose from the action

by a feminist protest group, Bread and Roses

that was seeking a place to situate a women’s center for under-served

women in Cambridge. On March 6, 1971, the women marched and took over a former

industrial building at 888 Memorial Drive, which was then owned by Harvard.

While occupying the building, the women offered free child care and classes

for women. After ten days they were forced out, but the protest sparked community

interest that led to the purchase of a house at 46 Pleasant Street in Cambridge.

The Women's Center (later incorporated as the Women's Educational Center) opened

in January 1972 in the house at 46 Pleasant Street. It was committed to the

philosophy that empowered women could help themselves and effect change in their

communities.

Staffed mostly by volunteers, the Women's Center

provides women with referrals to outside community resources, including doctors,

therapists, lawyers, clinics, housing and job opportunities. Its newest project,

Women of Action, organizes women to fight for their rights, most recently insisting

that the MBTA stop to pick up women with children in baby carriages. Some groups

that began by meeting at the Women's Educational Center, developed into independent

organizations, including the Boston Area Rape Crisis Center, Finex House, Incest

Resources, and Transition House, a shelter for women and children. Archives

from 1971 to 1988 are held at Northeastern University Library.

References: Finding

Aid, Northeastern University Library Archives; Annie Popkin Papers, Schlesinger

Library; Central Square Women's Walking Tour.

Return

to Top of Page

Women’s

Coffeehouse (flourished 1979-ca. 1989)

Feminist community coffeehouse

The Women's Coffeehouse was organized in October

1979 when a small group of women from the Women's Center

in Cambridge, Massachusetts met to discuss plans to open a coffeehouse operated

by and for women. The stated objective of the Women's Coffeehouse was to provide

"an active, participative, grass roots environment" (The Women's Coffeehouse,

Event Schedule, February-April 1989) where local women to develop their own

community despite their personal political affiliations. Weekly performances

were intended to spark discourse among women in the community about their shared

issues and concerns. They realized that women of all ages, nationalities, body

types, economic status, and disabilities lacked a space to safely enjoy cultural

activities together.

The first Coffeehouse event was held in December

1979 and featured Marjorie Parsons as the guest speaker. For the next ten years

the Coffeehouse remained open, sponsoring performances that included local musicians,

writers, speakers and activists such as Hillary Kay, Nancy Aberle, Beth Hodges,

Linda Brown, Pamela Gray, Sharon Kennedy, and Betsy Zelchin. These weekly performances

were intended to spark discussions among women in the community in order to

share their issues and concerns. Although the core organizers of the Women's

Coffeehouse were feminists, they were careful to reach out to and welcome all

women. The archives held by the Northeastern University Library documents the

organization and activities of the Women's Coffeehouse and contains meeting

minutes, photos, fliers, and audiotapes of performances and press releases.

Source: Dominique Tremblay, finding aid for the Women’s

Coffeehouse Records, prepared October 2006. Northeastern University Library

http://repository.neu.edu/items/neu:17714.

Return

to Top of Page

Women’s

Community Health Center (1974 - 1981)

Woman-owned health and education center

Conceived in 1973, the same year of the landmark Supreme Court decision affirming a women’s right to an abortion, the Women’s Community Health Center was organized by Cookie Avrin, Jennifer Burgess, and Terry Plumb, along with many others. In 1974, WCHC acquired a physical space at 137 Hampshire Street and incorporated as a non-profit. The goal was to offer a woman controlled and owned health center for education, prevention, and health services. For seven years, WCHC gave women tools to gain control of their health, health care, and lives. Though Roe v. Wade affirmed the legal right to abortion, the decision did not create widespread access to abortion. Many of the abortion services were developed at women-owned clinics created to provide holistic women’s health care. The Women’s Community Health Center in Cambridge, the Vermont Women’s Health Center, and New Hampshire Women’s Health Services were some of the first clinics created to provide healthcare for and by women as alternatives to the traditional medical system. Upon arriving at the WCHC, people completed a “herstory” form to share information about family medical history, current needs, and preferences for care. They’d meet a health worker who was committed to incorporating health education into every step of medical care, primarily through demonstration (“self-help”). For a breast or cervical exam, health workers first demonstrated on themselves. Patients, in front of the health worker, could practice what they learned to make sure they got it right. They could opt to have a doctor perform the exam.

The organizers believed that health care should not be provided for a profit. Rather than a predetermined sliding scale, there was a suggested fee system. Funding came from community support, including performances with local poets and singers, a $5000 grant from the Boston Women’s Health Book Collective (which authored Our Bodies, Ourselves), and the sale of speculums to the general public.

WCHC translated all literature into Spanish and Portuguese and offered Spanish-speaking and lesbian self-help and groups. From 1975-76, members of the collective instructed Harvard Medical School students on the pelvic exam after “local women medical students requested the program to change the inadequate and oppressive methods usually employed in pelvic instruction.” (Women’s Community Health Center Second Annual Report).

WCHC provided essential services to women, including abortions and gynecological care. It operated with a physician’s license and employed women doctors. In March of 1975, the center began a frustrating process of applying for a clinic license, which wouldn’t be granted until January of 1981, only months before WCHC had to close its doors. Fenway Community Health Center provided followup care to WCHC patient. Becoming the only women owned licensed clinic in the state was a success but came with staff burnout and public criticism. The work of WCHC lived on through the community members engaged with the center.

References:

The Women’s Community Health Center archive is housed at Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute.

Written by Kimm Topping, printed in Mapping Feminist Cambridge guidebook, 2019: https://www.cambridgewomenscommission.org/download/CCSW_MFCamb_book_190717.pdf

Return

to Top of Page

Women’s Law Collective (1970s)

Woman-led law collective

The Women’s Law Collective started at 678 Massachusetts Avenue and relocated to 187 Hampshire Street in 1982. It was one of many law collectives in Cambridge and Boston at the time, but the only one led entirely by women. The collective started as a course, “Women and the Law,” with law students as founding members. Their goal was to raise women’s awareness about laws related to their everyday lives. They provided representation for cases such as divorce, abortion, workers’ rights, and welfare.

While several iterations of the group existed over the years, Holly Ladd led the Hampshire Street collective in the early 1980s. The Women’s Law Collective’s work addressed legal issues which impact women and families today. Notably, it co-drafted the Abuse Prevention Act, which allows domestic violence survivors access to restraining orders and other supports. Lawyers in the collective represented Our Bodies Ourselves, workers’ unions, and same-gender couples before the marriage equality act.

The collective contributed to the revival of the National Lawyers Guild in Massachusetts, which now supports local activists and works to eradicate racism and other forms of discrimination. The Women’s Law Collective eventually dissolved (date not available).

A history of 1970s law collectives from the National Lawyers Guild Massachusetts Chapter describes law communes as, “These communes practiced law in a new way, involving themselves directly in anti-war and community work as participants on the front lines. They rejected all hierarchy – especially distinctions between lawyers and non-lawyers. They functioned as the groups they served: egalitarian collectives making decisions by consensus. The lawyers rejected class distinctions, taking turns answering the phones while sharing desks and administrative tasks.” Students from Harvard and Boston University started the first law communes in Central Square, Cambridge, later joined by The Women’s Law Collective. Radical Boston College law students met informally in a church in Boston’s South End while another law collective was formed in Dorchester."

References: Written by Kimm Topping, printed in Mapping Feminist Cambridge guidebook, 2019: https://www.cambridgewomenscommission.org/download/CCSW_MFCamb_book_190717.pdf

www.nlgmass.org/nlg-mass-history

Return

to Top of Page

Women’s

School of Cambridge (1971-1992)

The Women’s School was established in 1971

by twenty women who were involved with the Women’s

Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The school was founded as an alternative

source of feminist education, and its ideologies were based on socialist feminism.

It was operated as a collective with classes taught by volunteer teachers. All

collective members, students, and teachers were women. Registration fees were

kept low so that all women would be able to participate. In 1973, the collective

developed a formal administrative structure. Committees were created to select

courses, develop special projects, and handle office work and finances. Classes

were offered on anti-racism, auto mechanics, growing up female, international

women’s struggles, lesbianism, Marxism, women’s aging, and many

other topics. The Women’s School closed in 1992. It was the longest running

women’s school of its type in the United States. The archive of the school,

as well as its library, is held in the Special Collections of the Library at

Northeastern University, Boston.

References: Special Collections, Northeastern University, Boston.

Online guide;

The Women’s History Tour of Cambridge

Return

to Top of Page

Return to Alphabetical Index

Cambridge

Women's Heritage Project

June 2020

Julia

Abernethy Wallace was the daughter of Ethel (Thomas) and Walter Eugene Abernethy.

She grew up in Shelby, North Carolina. She attended Meredith College in Raleigh,

where she met her future husband, James (Jim) Wallace with whom she shared a

life-long commitment to social justice and instilled the same values with their

children. She accompanied Jim to Cornell University, then to Los Angeles, where

she worked as a youth advisor at a local church. The family then moved to Buffalo,

New York, where Julia received a Masters degree in education. After they moved

to Cambridge, she obtained a second Masters as a reading specialist and then

taught remedial reading for many years in the Cambridge public schools.

Julia

Abernethy Wallace was the daughter of Ethel (Thomas) and Walter Eugene Abernethy.

She grew up in Shelby, North Carolina. She attended Meredith College in Raleigh,

where she met her future husband, James (Jim) Wallace with whom she shared a

life-long commitment to social justice and instilled the same values with their

children. She accompanied Jim to Cornell University, then to Los Angeles, where

she worked as a youth advisor at a local church. The family then moved to Buffalo,

New York, where Julia received a Masters degree in education. After they moved

to Cambridge, she obtained a second Masters as a reading specialist and then

taught remedial reading for many years in the Cambridge public schools.  Betsy

Warrior was a radical activist and organizer of women’s liberation and

the battered women’s movements in Cambridge, Boston and the nation. In

1968 she began organizing and agitating as one of three original members of

Cell 16, a women’s liberation group that exposed the subordination of

women and advocated for equal pay, childcare, reproductive rights, economic

justice and self-defense. These early messengers for women’s rights campaigned

against unpaid labor by homemakers, wife abuse, exposed the inequality of women

in the workforce and in intimate relationships and they trained women in karate

for self-protection. She was an author and editor of the Journals of Female

Liberation.

Betsy

Warrior was a radical activist and organizer of women’s liberation and

the battered women’s movements in Cambridge, Boston and the nation. In

1968 she began organizing and agitating as one of three original members of

Cell 16, a women’s liberation group that exposed the subordination of

women and advocated for equal pay, childcare, reproductive rights, economic

justice and self-defense. These early messengers for women’s rights campaigned

against unpaid labor by homemakers, wife abuse, exposed the inequality of women

in the workforce and in intimate relationships and they trained women in karate

for self-protection. She was an author and editor of the Journals of Female

Liberation.  Florence Josephine Lee was born on 4 September 1862 in Canton, New York, to

John Stebbins Lee (born in Vermont in 1820) and Elmina (Bennett) Lee (born in

New Hampshire in 1821). John S. Lee was Principal of the Preparatory Department

at St. Lawrence University in Canton, which helped to prepare students for the

university’s Theological School. (Florence’s brother, John, later

became the university's president.) Oddly, a fraternity that now occupies the

Lee family's Canton house claimed Florence as its resident ghost, believing

she had died there tragically and her “mischievous, teasing wraith”

haunted the house. In fact, Florence was a graduate of St. Lawrence and later

a member of its board of trustees. Whitman Hall on the campus is named for her

and her husband.

Florence Josephine Lee was born on 4 September 1862 in Canton, New York, to

John Stebbins Lee (born in Vermont in 1820) and Elmina (Bennett) Lee (born in

New Hampshire in 1821). John S. Lee was Principal of the Preparatory Department

at St. Lawrence University in Canton, which helped to prepare students for the

university’s Theological School. (Florence’s brother, John, later

became the university's president.) Oddly, a fraternity that now occupies the

Lee family's Canton house claimed Florence as its resident ghost, believing

she had died there tragically and her “mischievous, teasing wraith”

haunted the house. In fact, Florence was a graduate of St. Lawrence and later

a member of its board of trustees. Whitman Hall on the campus is named for her

and her husband. Born

in Cambridge on Howard Street, Antoinette (Toni) Rinaldi’s family moved

to Western Avenue in 1927. She attended Houghton Grammar School until 1935 and

then Cambridge High and Latin School from 1935-1939. Toni was a USO hostess

at the Cambridge Neighborhood House, then at 79 Moore Street, from May 1942

to July 1945. She met her husband, Irvin Williams, at the first dance, and they

were married on July 22, 1945. During the Second World War, Toni worked at the

silk mill in Brighton, where she wound thread for gunpowder bags, and at Dewey

and Almy Chemical Co. in Cambridge, making and inspecting target practice balloons.

She also worked at American Science & Engineering, Honeywell, and Bentley

and Babson colleges until her retirement in 1964.

Born

in Cambridge on Howard Street, Antoinette (Toni) Rinaldi’s family moved

to Western Avenue in 1927. She attended Houghton Grammar School until 1935 and

then Cambridge High and Latin School from 1935-1939. Toni was a USO hostess

at the Cambridge Neighborhood House, then at 79 Moore Street, from May 1942

to July 1945. She met her husband, Irvin Williams, at the first dance, and they

were married on July 22, 1945. During the Second World War, Toni worked at the

silk mill in Brighton, where she wound thread for gunpowder bags, and at Dewey

and Almy Chemical Co. in Cambridge, making and inspecting target practice balloons.

She also worked at American Science & Engineering, Honeywell, and Bentley

and Babson colleges until her retirement in 1964. Pearl

Katz, the daughter of Julius Katz, was born in Kovno, Russia, in 1900 or 1901.

She emigrated with her mother and two older siblings to Connecticut in 1905,

where her father later joined them. Although she went only through high school,

she was self-educated to a remarkable degree. In 1921, the family moved to Cambridge,

and in 1927 she married a young lawyer, Henry Wise. They had three children

(two daughters and a son) who attended Cambridge schools. Beginning in 1942,

Wise became involved in public affairs. She served first as president of the

League of Women Voters of Cambridge (1942-1945). In 1945, she organized the

Parent-Teachers Association at Cambridge High and Latin School and was its first

president in 1947, working successfully to obtain federally funded hot lunches

in the schools. In 1948, she organized and led the statewide legislative campaign

of the Massachusetts League of Women Voters, fighting to allow women to sit

on juries in the Massachusetts courts. In 1945, she was elected to the Cambridge

School Committee, on which she served for three terms from 1949 to 1955. For

one of the three terms, she was the vice chair.

Pearl

Katz, the daughter of Julius Katz, was born in Kovno, Russia, in 1900 or 1901.

She emigrated with her mother and two older siblings to Connecticut in 1905,

where her father later joined them. Although she went only through high school,

she was self-educated to a remarkable degree. In 1921, the family moved to Cambridge,

and in 1927 she married a young lawyer, Henry Wise. They had three children

(two daughters and a son) who attended Cambridge schools. Beginning in 1942,

Wise became involved in public affairs. She served first as president of the

League of Women Voters of Cambridge (1942-1945). In 1945, she organized the

Parent-Teachers Association at Cambridge High and Latin School and was its first

president in 1947, working successfully to obtain federally funded hot lunches

in the schools. In 1948, she organized and led the statewide legislative campaign

of the Massachusetts League of Women Voters, fighting to allow women to sit

on juries in the Massachusetts courts. In 1945, she was elected to the Cambridge

School Committee, on which she served for three terms from 1949 to 1955. For

one of the three terms, she was the vice chair.